Making your 1st Chrome / Brave Extension....

By Strictly-Software

This article is about how to go ahead and make your first extension for Brave, Chrome, or Edge. As I no longer use Chrome but use Brave instead which like Microsoft Edge is based on the core Chromium Open Source standards-compliant browser, any mention of Brave in this article can be applied to Chrome or Edge as well.

The good thing about choosing to write your first extension for a Chromium-based browser is that once you have done it, it can be applied to 3 major browsers, Chrome, Brave, and Microsoft's replacement for Internet Explorer, Edge. So if you want to maximize your efforts choosing to develop an extension for Chromium gives you much more scope to apply it to other major browsers unlike Mozilla for Firefox.

Not only do I like Brave for paying me not any site owner, to watch adverts in cryptocurrency (BAT), it is more secure, with an easy way to allow or prevent tracking cookies, 3rd party cookies, scripts, adverts, popups, and more from following you around the web.

It does this by stripping out all the tracking codes by default before rendering the page.

By doing this it also saves bandwidth and therefore time. It also uses TOR as it's an incognito window so you are more secure when trying to avoid people by going through the onion to access many pages that Brave will sometimes automatically redirect you to.

You can download the Brave Browser from this link and start to strip trackers and earn cryptocurrency for ignoring tiny little adverts that are shown to you in the corner of the screen right now.

Setting Up Your Extension

1. Create a folder somewhere on your machine where all the files for the extension will be located. I just created a folder in documents called "Extensions" and then within it for this test a "HelloWorld" sub folder.

2. Create a manifest.json file with basic info about your extension. The manifest.json file tells Chrome important information about your extension, like its name and which permissions it needs.

The manifest version should always be 2, because version 1 is unsupported as of January 2014. So far our extension does absolutely nothing, but let’s load it into Chrome / Brave anyway.

Let's add some info into it which describes the extension.

{

"manifest_version": 2,

"description": "Hello World Extension",

"name": "Strictly-Software Hello World Extension",

"version": "0.1.1"

}

3. Create a content script which is "a JavaScript file that runs in the context of web pages." This means that a content script can interact with web pages that the browser visits.

So open a text file and make the script, as we are doing a hello world all we need to do is something simple such as showing an alert box whenever we go to a new URL that shows a message e.g:

// content.js

alert("Hello from Strictly-Softwares Brave/Chrome extension!");

Save the file in the same folder as all of your other files as content.js.

As we want the alert box to show on every URL we access we need to add a bit of script in the manifest file which tells it to act on <all_urls> you can see this in the below example as we also tell the manifest.json file about our JavaScript that needs to run on all the URLS we access.

{

"manifest_version": 2,

"description": "Hello World Extension",

"name": "Strictly-Software Hello World Extension",

"version": "0.1.2022"

"content_scripts": [

{

"matches": [

"<all_urls>"

],

"js": ["content.js"]

}

]

}

If we wanted the extension code to only run on certain pages then we can use regular expression like syntax which you can explore later to define the URLS that our code acts on.

Also if we were loading multiple JS files into our manifest file, we would use commas within the square brackets to denote them e.g to add jQuery go and get the version of the plugin you want e.g from https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/3.3.1/jquery.min.js and save a local copy into your extension folder.

There is no point loading it from a remote site each time as it takes time to load, plus they have stopped using the "latest" version in their filename which you used to be able to reference to get the most up to date version from Google's or jQuery's CDN, however they stopped it due to the amount of requests they were getting which was almost on an unintentional DOS scale.

For framework files you should always get a version that you know works, and save it locally or on a CDN, so that it can be cached and not loaded from a remote site each time. Also there is no need to keep updating it to the next version when one comes out. If it works for the project you are working on then leave the script reference alone.

This is something many developers didn't understand by always loading in the latest version remotely, this took network calls, time to load, and it often introduced new bugs into their code. It is far better to store all your code locally so it can be cached and so that you know it works. So to add jQuery into the extension we would do this.

"js": ["jquery-3.3.1.js", "content.js"]

The manifest would look like this if you did add extra files in e.g:

{

"manifest_version": 2,

"description": "Hello World Extension",

"name": "Strictly-Software UserAgent Extension",

"version": "0.1.2022",

"content_scripts": [

{

"matches": [

"<all_urls>"

],

"js": ["jquery-3.3.1.js", "lightbox.js", "scripts.js", "content.js"]

}

]

}

4. Add a logo for your extension at the size of 24x24 this will appear in your toolbar when you pin it so you can use the extension. At the same time make some more icons that will be used on the brave://extensions/ page when loading up your extension, for example when you click on it to see the details (Name, description, version etc), and elsewhere.

You can use this page to convert an image, screenshot, logo into the sizes you need > https://icoconvert.com/.

The icon for the toolbar should be called just icon.png which you can put in the same folder as the other images which you should name with the size on to not get confused.

At the same time make .png logos of the sizes 16x16, 48x48 and 128x128. These are put at the top level in the manifest as you can see below as they are used in different places. The toolbar icon is down at the bottom as you can see.

So the final manifest file will look like this.

{

"manifest_version": 2,

"description": "Hello World Extension",

"name": "Strictly-Software UserAgent Extension",

"version": "0.1.2022",

"icons": {

"16": "icon16.png",

"48": "icon48.png",

"128": "icon128.png"

},

"content_scripts": [

{

"matches": [

"<all_urls>"

],

"js": ["content.js"]

}

],

"browser_action": {

"default_icon": "icon.png"

}

}

5. Now in Brave/Chrome go to extensions and open it up.

In Brave it will be a URL like brave://extensions/ and Chrome chrome://extensions/. In the top right corner turn developer mode on.

Then in the top left corner hit the "Load Unpacked" button and select your folder containing all your files and images.

You will see your extension appear in the list of already loaded extensions with one of your logos showing e.g:

5. Clicking on "Details" will show the information from your manifest and a different size logo e.g:

6. Now select the extension icon in the toolbar to get up your drop down menu of extensions and select the pin so it's pinned to your toolbar e.g:

7. Now try going to any URL and you should get an alert box pop up straight away with the message you put in the content.js file. Even before other JavaScript loaded content fires from a DOM or Window onload event, this alert should fire straight away e.g:

8. And there you go, your first Chrome/Brave extension. Obviously, this just a Hello World test showing you how you can create a basic extension and if you are going to make an extension you will need to read up more on all the different features and actions possible.

However, this is a good guide for someone wondering about how to make an extension or insert code that fires before the page is loaded.

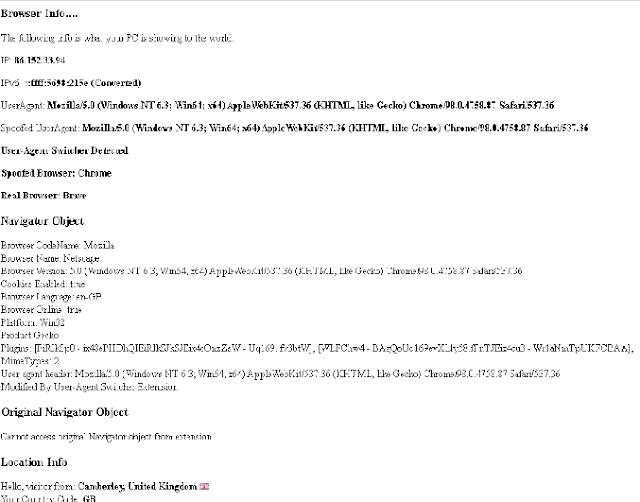

I have an idea for what I need to use this for such as overwriting JavaScript objects and putting my own properties into them so that they load when the page does before any other JavaScript code as well as being accessible to any local code that tries to access them. You can read a bit about this in a later article, injecting a script at the top of your HTML page.

If you want more information about what you can do just head to the main Chrome extensions page for developers at https://developer.chrome.com/docs/extensions.

Have fun...

By Strictly-Software