How Can We Test For Brave?

By Strictly-Software

The problem with detecting the Brave browser which I use most of the time is that it hides as Chrome and doesn't have its own user agent. It used to, and the hope is that in the future it will again but at the moment it just shows a Chrome user-agent.

For example, my latest Brave user-agent is:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/97.0.4692.99 Safari/537.36

It also apparently used to have a property on the windows object

window.Brave which is no longer there anymore. I have read many articles on

StackOverflow about detecting Brave and all the various methods that apparently used to work don't anymore due to objects and properties such as

window.google and

window.googletag no longer exists on the windows object.

As these posts were not written that long ago it seems that there have been a lot of changes on the window object by Chrome / Google / Brave etc. So when writing your own function as I did it is worth outputting all the keys on the window object first to see what is there and what isn't e.g.

const keys = Object.keys(window);

console.log(keys);

This just outputs all the keys such as events, other objects like document and navigator, and properties as well into the developer tools console area that all modern browsers have.

As Brave, Edge, Opera and Chrome are all based on the same Chromium browser they are basically the same standard-compliant browsers.

Remember we should always use feature detection rather than user-agent parsing to choose whether or not to do something in JavaScript but it is amazing when using a user-agent switcher how many modern-day sites break when I change a standards-compliant browsers agent string to IE 6 for example.

If the coder wrote their code properly it wouldn't matter if I changed the latest version of Chromes user-agent to IE 6 or even IE 4 or Netscape Navigator 4, all sites should work perfectly as instead of doing old school tests like

isIe = document.all;

isNet = document.layers;

And then branching off those two as we did in the old days of scripting which led to browsers like Opera which no one catered for, having to support both IE and Netscape event handlers and pretending to not exist. However, they did eventually add the Opera property to the window object so if you really wanted to find it you could just test for:

if(window.opera){

alert("This is Opera");

}

However, this no longer exists and Opera uses the same WebKit Chromium base as all the other modern browsers apart from Firefox.

Also, remember that the issue with JavaScript is that every object can be overwritten or modified, that is why we have user-agent switchers in the first place because they can, and do overwrite and change the window.navigator object.

Therefore if you are really pedantic there is NO real way to test if anything is real in JavaScript as a plugin or injected script could have added properties to the Window object such as changing the user-agent or adding a property another browser uses to the window so that tests for window.chrome fail in FireFox because you have created a window.chrome property FireFox detects.

There are loads of ifs and buts and we can discuss the best approach all day due to injected code and extensions overwriting objects or accidental setting of objects by forgetting to do == and accidentally setting a variable or object with a single = by mistake, but let's answer the question,

I have read a lot about people trying to detect Brave and a lot of old objects on the Chrome browser like window.google and window.googletag that no longer exist or even window.Brave which apparently existed on the window object at one stage.

Why might you want to even detect Brave if it is a standards-compliant Browser and you are doing feature detection and not user-agent sniffing anyway you might ask?

Well good question, if you are writing your code properly you shouldn't ever need to know what Browser the code is running in as it will work whatever the user is running your web page in due to proper use of feature detection.

However, you may have a site that wants to direct people to the right extension depository or download the correct add-on. Therefore to make the user comfortable in their decision you might want to show that you know what browser the user has so that they are happy downloading the add-on.

Or there might be a myriad of other reasons such as

asking users to update their browser due to an exploit that has been discovered or to

ask old people still using IE6 to upgrade to a modern browser. Also if you want them to use one that removes

cookies, trackers, and adverts, and is

security conscious, you may want to

direct non-Brave users to the

Brave download page.

Therefore the function I have come up with tries to future proof by hoping Brave does put its name into the user-agent at some point, and it checks for the existence of properties in objects such as the window or navigator object.

You can put all your complaints and ideas for improving this function for detecting Brave in the comments section and maybe we can come up with a better solution.

// pass or don't pass in a user-agent if none is passed in it will get the current navigator agent

function IsBrave(ua){

var isBrave = false;

ua = (ua === null || ua === undefined) ? ua = window.navigator.userAgent : ua;

ua = ua.toLowerCase();

// make sure it's not Mozilla

if("mozInnerScreenX" in window){

return isBrave;

}else{

// everything in JavaScript is over writable we could do this to pass the next test

// but then where would we stop as every object even window/navigator can be overwritten or changed...?

// window.chrome="mozilla";

// window.webkitStorageInfo = "mozilla";

// make sure its chrome and webkit

if("chrome" in window && "webkitStorageInfo" in window){

// it looks like Chrome and has webkit

if("brave" in navigator && "isBrave" in navigator.brave){

isBrave = true;

// test for Brave another way the way the framwwork Prototype checks for it

}else if(Object.prototype.toString.call(navigator.brave) == '[object Brave]'){

isBrave = true;

// have they put brave back in window object like they used to

}else if("Brave" in window){

isBrave = true;

// hope one day they put brave into the user-agent

}else if(ua.indexOf("brave") > -1){

isBrave = true;

// make sure there is no mention of Opera or Edge in UA

}else if(/chrome|crios/.test(ua) && /edge?|opera|opr\//.test(ua) && !navigator.brave){

isBrave = false;

}

}

return isBrave;

}

}

Of course if you really didn't want all these fallback tests and hope that Brave will sort their own user-agent out in the future or re-add a property to the window object as they apparently used to then you could just do something like this:

var w=window,n=w.navigator; // shorten key objects

let isBrave = !("mozInnerScreenX" in w) && ("chrome" in w && "webkitStorageInfo" in w && "brave" in n && "isBrave" in n.brave) ? true : false;

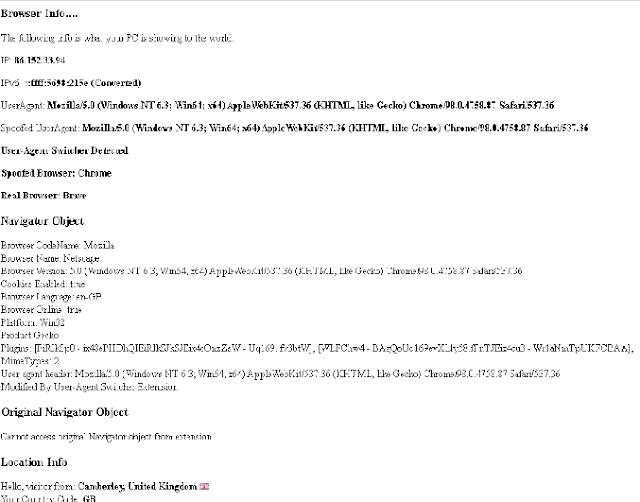

Just to show you that it works here is the "Browser" test page I keep on all my Browser's bookmark bars, written using just JavaScript with some AJAX calls and my own functions which lets me see the following info:

- My Current IPv4 address by calling a URL that only returns IPv4.

- My Current IPv6 address by calling a URL that will return one if I am using one, otherwise it converts the IPv4 into an IPv6 address format. Obviously, this is not my real IPv6 address as if I had one it would be returned it is just the IPv4 address converted into IPv6 format.

- The UserAgent that the browser is showing me, this may be spoofed if a user-agent switcher is being used.

- The real User-Agent if a spoofed user-agent is being used by a user-agent switcher extension/add-on.

- The spoofed Browser Name.

- The real Browser name.

- Whether a user-agent switcher was detected. I have my own which does both the Request Header as well as overwriting the window.navigator object with different agents details. It creates a copy of the original navigator object so I can output it as well as the spoofed version.

- An output of the current window.navigator object, if a user-agent switcher was used it will show the overwritten navigator object.

- An output of the original window.navigator object if my own user-agent switcher was used then I create a copy of the same navigator string displayed for the current navigator object so both the spoofed and real navigator objects are outputted.

- A script that loads in info about my location based on my IP address e.g: Town, County, Country, ISP, Hostname, Longitude, and Latitude.

Example Browser Test Output

If you look at this image, double click to open bigger if you need to, although it won't show you all the ISP & Location info at the bottom, it will show you the user-agents, both spoofed and real, as well as the spoofed browser and the real browser, which my custom function detects from either just a user-agent string or with the IsBrave() function I outputted above.

You can see here that although the user-agent strings are exactly the same my code that detects the browser has correctly recognised the real browser as Brave by using the function this article is about and for the spoofed Browser name it shows Chrome, which is the browser Brave tries to mask itself as.

This handy little script is on all my browsers bookmark bars for easy access and I find it very helpful for quickly seeing if a user-agent switcher is enabled and what if any, my browser it is pretending to be, as well as my current GEO-IP location in case I am using a global VPN, TOR, Opera or a proxy.

Let me know what you think of this function tested in Firefox, Chrome, Opera, Edge and of course Brave.

By Strictly-Software